Life Of Dard Hunter

William Joseph “Dard” Hunter was born in Steubenville, Ohio in 1883 at the height of the industrial revolution His father, William Henry Hunter, was an ardent proponent of modern advances such as the automobile, but he was equally concerned that hand crafts not be sacrificed in the name of progress. The elder Hunter was a newspaper owner and publisher, amateur woodcarver, and, from 1891-1895, owned a portion of the Lonhuda Art Pottery Company.

From an early age, Hunter was immersed with the techniques of printing at his fatherís newspaper and often set lines of type by hand as a young adult. His artistic abilities were first evidenced in 1900 when his father moved the family to Chillicothe, Ohio to operate another newspaper and hired Dard to be the staff artist. It was also at this time that his given name of William Joseph would then be forever shortened to the family nickname of just “Dard”.

Hunter soon became restless with the newspaper business and joined his brother Philip who was a very accomplished magician and known throughout the country as “Phil the Wizard“. Dard’s role as chalk-talker would serve to entertain the audience between acts.

Hunter soon became restless with the newspaper business and joined his brother Philip who was a very accomplished magician and known throughout the country as “Phil the Wizard“. Dard’s role as chalk-talker would serve to entertain the audience between acts.

In 1903, travels with his prestidigitation pursuits brought him to Riverside, California where he stayed at the New Glenwood Hotel (now The Mission Inn), one of the first hotels fashioned in the Arts & Crafts style. This was his first introduction to the Mission Style in art and design and it would change his life.

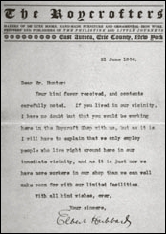

In June of 1904, Dard applied for a summer position with Elbert Hubbard and the Roycrofters. He was denied employment but insisted he could do the job and in July he simply showed up at the artist’s colony and was hired. Within a few months, he was designing stained glass for windows in the Roycroft Inn and title pages for Hubbard’s press. Initially, many of his designs were based on earlier newspaper efforts such as the 1903 Ohio History piece seen above. In his spare time, Hunter perused journals such as Deutsche Kunst und Dekoration, gaining a sense of design in the Viennese fashion.

In 1908, Dard married Roycroft pianist Edith Cornell. At the time, he was so enamored with the work of Josef Hoffman and the Wiener Werkstatte that they spent their honeymoon in Vienna. For the next few years, Hunter incorporated the geometric patterns and highly stylized figures into his work with the Roycrofters.

Hunter’s designs for books, leather, glass and metal helped unify the Roycroft product line and distinguish it from that of other American Arts & Crafts enterprises. Hunter also experimented with pottery, jewelry, and furniture and had a successful correspondence school with The Dard Hunter School of Handicrafts. The brochure, Things You Can Make, offered kits for jewelry. Disillusioned with the commercialism of the Roycrofters and eager to set out on his own, Hunter returned to Vienna in 1910. After taking courses in lithography, book decoration, and letter design at the K. K. Graphische Lehrund Versuchsanstalt (Royal-Imperial Graphic Teaching and Experimental Institute), he then moved to London. There he was successful in finding work with the Norfolk Studios designing books and advertising literature.

On a spring day in 1911, Hunter wandered into the London Science Museum and saw an exhibit of hand papermaking moulds and watermarks, steel punches, copper matrices and hand-held type casting moulds. This experience inspired him to learn more about these centuries-old arts. Another change was about to occur in his life for he was then challenged to begin experimenting with the techniques of making paper by hand. Click here for Part II.